Orangutans of Borneo struggle on an archipelago of wildlife reserves that are isolated by vast monoculture plantations. The best way to help the ”man of the forest” is to plant a tree.

Text by Ville Palonen and Yaroslava Troynich

Photos by Ville Palonen

Humidity in the jungle is so thick it could be cut with a machete. Crowd on an elevated platform stares at the jungle canopy, cameras ready. Shirts glue slowly to sweaty backs, but everybody waits patiently as minutes pass by. Someone swats a mosquito, others whisper in hushed voices. In the forest, birds chirp and cicadas buzz loudly.

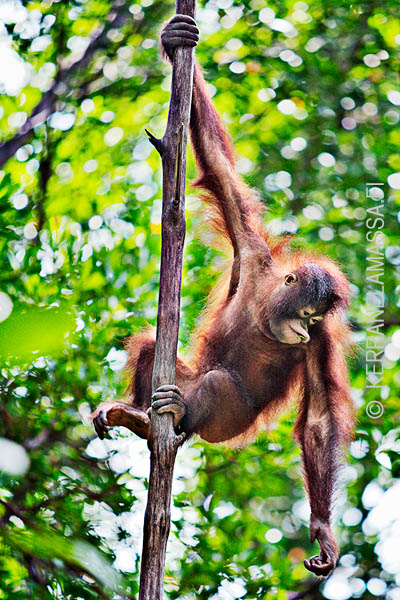

A sudden crash electrifies everyone. A treetop starts shaking, then another. When a reddish shape flashes through the thick foliage, crowd lets out an excited sigh. It’s an orangutan!

One can only marvel at how effortlessly the creature moves through the forest. The furry ape doesn’t leap from a branch to another like monkeys. The only tree-dwelling ape in the world, she simply sways a tree until she reaches the next one with her long arms.

The furry ape doesn’t leap from a branch to another like monkeys. She simply sways a tree until she reaches the next one with her long arms.

Long reach is useful for pranking, too. After a while the curious juvenile appears next to the crowded viewing platform. When tourists get closer, thrilled with this rare encounter, she makes her move. Like a lightning she steps forward, reaches out and snatches a hat. A greying gentleman from Cambridge can only look on as the rascal climbs back to canopy and starts fitting his brimmed hat on her head. ”My friends back home will never believe this”, the man repeats baffled.

Orangutan orphanage

The incident may sound amusing, but it’s not. This baby orangutan, 4 years old Wulan, is being rehabilitated here at Rasa Ria Orangutan Centre in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Getting cheeky with humans doesn’t exactly help the effort.

”Orangutans are like small children, only more unpredictable”, explains Melvin George, a senior ranger. ”Sometimes they venture out from the centre and we need to fetch them back from a nearby village.”

Orangutans live with their mothers until they’re 7 years old, so Wulan and her tutor Katie wouldn’t survive in the wild on their own. Rasa Ria, just a 40-minute taxi ride from Sabah’s capital Kota Kinabalu, gives them a chance to learn in a safe environment how to climb and find food in the jungle.

Rangers provide supplement for their diet – mainly milk and fruits – twice a day, and small tourist groups can visit one-hour feeding sessions. The main purpose for tourism is educational: even locals may have never seen an orangutan. The centre takes only 140 visitors daily, and entrance fees are spend on wildlife conservation.

The main purpose for tourism is educational: even locals may have never seen an orangutan.

Rasa Ria Rehabilitation Centre was established in 1996 in collaboration with Sabah Wildlife Department, Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, and Shangri-La’s Rasa Ria Resort. The small patch of secondary rainforest is located next to a 5-star hotel and a golf course. Forest couldn’t support a wild population, but it suits fine for an orangutan nursery.

After feeding session is over and tourists have disappeared, we sit down with the ranger. Melvin George, 33, was trained at Sepilok and has worked at Rasa Ria for 8 years. He outlines how orangutan rehabilitation works. Orphans are brought to the centre couple of times per year. They are babies who have been kept as illegal pets or found at oil palm plantations after their mothers were killed.

Orangutans are rescued by Wildlife Rescue Unit, a 20-strong team funded by Malaysian Palm Oil Council and Rasa Ria Resort. After medical checkup and quarantine, apes begin the first stage of their rehabilitation. In 64-hectare reserve they learn how to climb, find food and built nests. When babies are 6 years old, they’re transferred to much larger Sepilok for next grade.

The aim of rehabilitation process is to teach orangutans how to survive in the wild. When they have learned the necessary practical and social skills – which takes years – they are released into Tabin Wildlife Reserve in East Sabah.

The aim of rehabilitation process is to teach orangutans how to survive in the wild.

”Babies become attached to people, so we try not to spend too much time with them”, George explains. ”But of course we are fond of them, too. Sometimes I visit Sepilok just to see how our babies are doing at their new home.”

Orphaned orangutans might be well taken care of, but wild populations struggle. Borneo, world’s third largest island, has lost 80% of it’s orangutans during the last century. During the last decade only, the decrease has been a whopping 30%.

Today, only 40 000 endangered apes survive in the wild, about quarter of them in Sabah.

Especially habitat loss – logging and clearing rainforest for plantations – has taken its toll. Surviving orangutans are isolated at an archipelago of small protected areas, separated by a vast sea of oil palm plantations.

One of the last refuges for Borneo’s wildlife is Kinabatangan River. It’s home to pygmy elephants, proboscis monkeys, orangutans – and humans who try to save them.

Welcome to the jungle

”Orangutans can survive in a logged rainforest, too”, says Mincho Kahar and points around. ”In this area, all hardwood was felled more than a decade ago. 30 orangutans still live here.”

Mincho, 30, is an conservationist and wildlife warden. He has promised to show us a wild orangutan, so we follow him through the swamp.

This forest, on a bank of Kinabatangan River, is not a postcard rainforest. There’s no sky-reaching dipterocarp trees around, and elephant paths criss-cross the thicket. Sweltering humid jungle is a hostile environment for unaccustomed. Sweat stings the eyes, rubber boots get stuck in knee-deep ponds of mud, and tiny but ferocious mosquitos attack relentlessly.

The most unnerving beasts of Borneo, tiger leeches, lay on ambush along the trail. If – or rather, when – these bloodthirsty creatures get a chance to crawl inside clothes and bloat themselves with blood, a classic joke can become reality: ”When you pull down your pants, there’s two of them. And the smaller one is your dick.”

When you pull down your pants, there’s two of them. And the smaller one is your dick.

That all is nothing but mild nuances. We’re here because this forest is the best place in Sabah to encounter a wild orangutan.

Mincho is guiding us through the 6-square-kilometer research site of HUTAN, a French non-profit organization which begun primate research in Kinabatangan in 1998. After the turn of the century their work expanded to wildlife conservation and community development projects, such as creating sustainable prawn traps for local fishermen and teaching environmental issues to school children.

Mincho knows this patch of jungle like the back of his hand. He worked for years as HUTAN’s research assistant, collecting data on orangutans. Mincho followed the elusive apes every day, from dawn to dusk, writing down their behavior on a data sheet every 3 minutes.

”Field work can get boring, because most of the time orangutans are just feeding or resting. But research assistants – all 15 of them are local guys – are motivated. They know that the data will help the whole conservation effort.”

For example, researchers learned that even though orangutans can cross smaller oil palm plantations, they get blocked by rivers. They don’t swim, so HUTAN created rope bridges over crocodile-infested waters.

The first rope bridge, made of recycled fire hose from Japan, was built in December 2005. Now there are 6 simple bridges hanging across the tributaries near the village of Sukau in Lower Kinabatangan.

Mincho explains that 20-30 years ago the biggest threat to orangutans in Kinabatangan river was poaching and capturing them for pet trade. Now apes struggle with forest fragmentation. Gigantic oil palm plantations have shattered the rainforest into smaller pieces.

Apes struggle with forest fragmentation. Gigantic oil palm plantations have shattered the rainforest into smaller pieces.

”Sabah’s oil palm plantations are 14 000 square kilometers – a size equal to 20 Singapores!” Mincho exclaims. ”Monoculture is the biggest threat to orangutans.”

All environmentalists agree that oil palm is in Borneo to stay, so the most important conservation issue is to unite the remaining forests. When wildlife populations are isolated from each other, a disaster like forest fire or disease outbreak can wipe out an entire population.

A few larger plantations have started to fund conservation projects, but Mincho argues that it’s nothing but greenwashing. ”Instead of donating money to organizations just to shut them up, they should give land. If a mere 100-meter strip of rainforest next to river bank would be left uninterrupted, elephants and other animals could travel past the plantations.”

Wild encounter

We trek through a thicket for an hour. Finally, after crossing a small stream by a rope bridge, Mincho signals us to stop. He points up to a rambutan tree. In the canopy, two dark shapes hang on branches.

Female and her juvenile baby are slowly peeling and eating furry rambutan fruits. These shaggy-haired creatures are completely different from the cute babies at the orangutan orphanage. They look wild.

We keep 20 meter distance. Mincho warns us not to go under the apes. ”They usually go to toilet before moving to a new ”restaurant” in the next fruit tree”, he whispers.

Ape diet consists of leaves, flowers, bark, honey, insects and most importantly over 300 kinds of fruit. They act as a major dispenser for many fruits. ”Seeds of some fruit trees don’t germinate unless they are first digested by an orangutan”, explains Mincho.

Orangutans are gardeners of the jungle. They know at least one thousand plants that are edible, inedible, poisonous, and beneficial. Scientists have reported that they eat herbs which kill parasites and which are used by indegenous people as a remedy for malaria or migraine.

Some orangutan populations use tools for foraging for food. They can learn new skills by watching others, and there are even signs of ”cultural traditions”.

Some orangutan populations use tools for foraging for food. They can learn new skills by watching others, and there are even signs of ”cultural traditions”. Separate orangutan populations may use same tools for different purposes, and skills are passed down through the generations. Some tricks – like using large leaves as an umbrella – might have been copied from humans.

”3 minutes left”, Mincho announces. HUTAN has a strict policy that visitors – only 300 per year – can spend maximum one hour with orangutans. It’s an exclusive experience: majority of tourists in Kinabatangan spot wildlife only from narrow cruise boats.

On the boat ride back to village Mincho points at river banks on both sides. The lush green forest has gaping holes, but some smaller clearings are filled with neat rows of trees tall as a man.

”One of the most important tools for wildlife conservation is forest replanting”, says Mincho. HUTAN works with environmental organizations like World Land Trust. They acquire small pieces of land, and hire teams of local women to plant trees and maintain the new mini-forests.

To save Kinabatangan’s orangutans, plenty of physical labour needs to be done. Tourists, too, can roll up their sleeves.

Saving saplings

Swinging a rusty 2-foot machete from left to right, right to left, is exhausting. It feels like playing tennis in a sauna, but wines and weeds that cover a small clearing must be shredded. Otherwise they suffocate saplings that were planted here a few months ago.

Persistent weed seems to re-unite with it’s roots as soon as one turns his sweaty back. Finally a fragile fruit tree appears under creeping wines. The work starts to feel rewarding right away. After a dozen years, an orangutan might built a nest in this tree!

”Weeding is very important. It multiplies the survival rate of saplings”, says Mark Louis Benedict, 29. He is the project co-ordinator of Ape Malaysia, a company that started to organize volunteering holidays in Kinabatangan in 2008. He is leading our small group of international volunteers in a tree planting lot half an hour’s boat ride upriver from Sukau.

Volunteers plant trees and get familiar with community projects like building sustainable prawn traps with local fishermen.

During a 12-day volunteering program participants plant trees and get familiar with community projects like building sustainable prawn traps with local fishermen. They also visit local elementary school, where they teach the importance of conservation.

Mark explains that Ape Malaysia tries to involve as many local people as possible. ”We hire boatmen for transportation, and volunteers eat their meals at homestays. It’s not the easiest or most profitable way to run a business, but we want to contribute to the community.”

Ape Malaysia also buys tree saplings from locals, who collect them from forest or their back yards. ”30% of our revenue goes to tree planting: saplings, machetes and grass cutters, hiring locals for maintainance work, and so on. Still, volunteers do most of the planting and weeding.”

Ape Malaysia’s work is part of a big picture called the Corridor of Life. The project, launched in 2002, aims to re-unite forest sanctuaries and other protected areas along Kinabatangan river. Organizations involved include WWF Malaysia and Sabah Wildlife Department, NGOs like HUTAN and MESCOT, eco-lodges, and even a few palm oil companies.

”If forest corridor is not connected, it’s almost impossible to see a future for Kinabatangan’s wildlife”, says Mark. ”But I believe the future is bright. In 15-20 years from now we will have a healthy forest here.”

Rainforest reward

After couple of hours of hard work our volunteer group has weeded the clearing and planted new saplings where previous ones have perished. It feels nothing but a gesture – so much more has to be done – but Mark points out the importance of our work.

”When a forest is good enough for orangutans, it’s good for all the other species, too. We’re even helping the sea turtles on Selingan island, because forest buffers on river banks prevent erosion and filter water.”

Our clothes are dirty and we’re dehydrated, but everyone is smiling. We’re making a difference, if only little by little.

When a forest is good enough for orangutans, it’s good for all the other species, too.

It’s time to get back for lunch in a village homestay. The boat ride is a great chance to spot wildlife, so we drive downstream slowly, watching the jungle pass by.

On the bank a faded sign warns about swimming: crocodiles lurk in these waters. A group of proboscis monkeys know the danger and are crossing the 50 meters wide tributary by a rope bridge. Pot bellied males with huge noses go first, adolescent monkeys follow. Extremely rare Storm’s stork sits an a branch above the water, and flock of hornbills, their majestic beaks silhouetting against the sky, glide across the river.

After reaching the main river we speed up. We zoom by an oil palm plantation that stretches until the river, and then our boatman suddenly slows down. He steers the boat towards a majestic assam-assam tree.

We raise our binoculars. In the canopy, orangutan mother is feeding. A tiny baby, not more than a couple of months old, clings on her fur. He stares at us, eyes round with amazement. On nearby branch a third orangutan, a juvenile, watches our boat.

It feels like the orangutan family has come to thank us for swinging our machetes. Watching these wild and free apes is our reward for helping the rainforest.

Sepilok Orangutan Sanctuary

Sepilok, world’s first orangutan centre, was set up in 1964. The facility’s objective is to rehabilitate orphaned orangutans, whose mothers usually have been slaughtered by poachers during forest clearing or after entering palm oil plantations. Sometimes plantation workers consider orangutans pests, so adults are killed and babies captured as pets.

Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, administered by Sabah Wildlife Department, is set on the edge of 43-square-kilometre Kabili-Sepilok Forest Reserve near Sandakan. Sanctuary’s wild orangutan population is estimated between 100-200. In 2012 the rehabilitation program had 47 apes.

In recent years only a couple of rescued babies were brought to the centre. This isn’t necessary good news; it might indicate that there’s no more orangutans living anywhere except in isolated wildlife reserves.

Rescued babies stay at the centre for several years. At the nursery they are taught essential skills which they mother would have taught them: how to climb, built nests and find food in a rainforest.

Around 700 red apes who have ”graduated” the program during the years have been released into the wild, mostly Tabin Wildlife Reserve in East Sabah.

Sepilok is one of Sabah’s tourism highlights and the most popular orangutan viewing place in the world. Every day it receives hundreds of visitors. Crowds are restricted to wooden walkways that lead couple of hundred meters inside a lush rainforest. From a viewing platform visitors can observe how rangers give semi-wild apes milk, bananas and other fruits. Most of the apes are still learning how to find food in the jungle, so they need supplement for their diet.

Some critics argue that Sepilok pays more attention to tourism business than orangutan rehabilitation. Without a question, tourism is a double-edged sword. Presence of hundreds of people clearly doesn’t help the orangutans settle in their natural habitat. On the other hand, without tourist dollars the rehabilitation centre might be left in despair.

PRACTICAL INFORMATION

Getting there

You can fly from Kuala Lumpur or Singapore to Kota Kinabalu and Sandakan with Air Asia (return trip costs about 200€). Sandakan has a daily minibus connection to Sukau village.

Tours and accommodation

Sabah has hundreds of travel agencies who organize almost identical tours. Below are some of the more environmental-conscious (and thus recommended) agencies and lodges.

Red Ape Encounters (RAE) is working in close co-operation with HUTAN in the village of Sukau. RAE can organize a visit to orangutan research site (120€) and arrange accommodation with a local family (10-20€ with meals). You can also book directly with Balai Kito Homestays.

S.I. Tours runs remote Abai Jungle Lodge along Kinabatangan River, halfway between Sandakan and Sukau. Guests can take short jungle walks and river cruises, and there’s a good chance of spotting wild orangutans. 2D1N package costs 240€.

An unforgettable way to experience Borneo’s rainforests is to stay at Uncle Tan’s Wildlife Adventures camp. 3D2N package costs about 110€ and icludes transportation from Sandakan, river cruises and jungle walks, and meals. Beware: the camp is spartan.

The fanciest resort around Kota Kinabalu is Rasa Ria Resort, which has an attached orangutan nursery. Non-residents, too, can visit the baby orangutans. Double room starts from 200€ per night.

Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre

Dozens of travel agencies run tours to Sepilok, but visiting independently is easy and much cheaper. Rehabilitation Centre is located half an hour’s ride from Sandakan town, and a one-way taxi fare is 10€. Entrance ticket is 9€ and camera permit 2,5€. The centre is open daily from 8am to 5pm. Feeding is twice per day (10am and 3pm) and between them it’s possible to have a lunch at cafeteria and take short walks along jungle trails.

Volunteering

Ape Malaysia runs 12-day volunteer programs in Sukau that start 21st every month. You can book a volunteer holiday (or a shorter customized visit) through Stockholm-based Good Travel. Their website is so far only in Swedish, but they’re happy to send information in English if you ask.