Kumbh Mela, India’s biggest religious festival, is a spectacular show. Mindboggling sights, sounds and smells are not for the faint-hearted.

Text by Ville Palonen and Yaroslava Troynich

Photos by Ville Palonen

At sunrise all hell breaks loose.

An army of naked men – there has to be at least two thousand of them – charges towards water calling out mantras. They are armed with swords, spears and tridents. Wild-eyed, dreadlocked, and wearing nothing but garlands around their necks and white ash rubbed on their bare skin, they remind of extras from a zombie flick.

They are sadhus, holy men, and behind them billows a tsunami of hollering devotees. Today is the most auspicious time to wash away sins in holy Ganges River, and everybody wants to take a dip at the same time.

Holy men have the right of way. The hectare-sized bathing area is fenced off by a chain of whistle-blowing policemen, who try to keep the millions-strong crowd of commoners at bay. Cops push and poke foreign journalists with long bamboo sticks like cattle, and one foolhardy photographer almost gets run over by a mounted officer.

In the mayhem the police line breaks and photographers sneak into the off-limits opening. After we’ve dodged scattered cops like a rugby players the mass of pilgrims swallows us. Crowd squeezes and pushes from all directions like hard-core fans in a rock concert. Humid air smells like sweat. The ground, even though covered with straws, turns into mud.

At this very moment this remote river bank is the holiest spot in India.

Festival of superlatives

Kumbh Mela is India’s most legendary festival. Every 3 years tens of millions of Hindu pilgrims congregate in four rotating locations – Nasik, Ujjain, Haridwar and Allahabad – to celebrate, listen to religious teachings, consult holy men, and bathe. It’s believed that during the most auspicious days, when planets are perfectly aligned, holy Ganges River can wash away sins.

Once in 12 years the massive gathering becomes colossal. This mega-festival, Maha Kumbh Mela, doesn’t lack superlatives. It’s the longest running religious festival in the world and the biggest gathering of people in the history of humankind. Officials estimate that in January-February 2013 the festival area in Allahabad was visited by astounding 120 million people. That’s the population of France and United Kingdom combined.

Mela grounds cover the intersection of India’s two holiest rivers, Ganges and Yamuna. Usually the 22-square-kilometre area is nothing but wasteland, covered with floods in monsoon season. But during a festival – even the annual Magh Mela, much smaller than Maha Kumbh Mela – this makeshift town has a population of millions.

Organizing such an event requires months of time and thousands of people. Roads and bridges have to be built. Visitors need electricity, firewood, toilets and drinking water. Festival area has it’s own hospitals, police stations, newspapers, and courts of law.

Sea of humanity

A stroll through Kumbh Mela is a baffling experience. Colossal pontoon bridges, made of metal plates and steel containers, cross the Ganges. On the east bank a pot-holed dirt road continues to the horizon without a single curve. Roadsides are occupied by camps with corrugated iron fences. Some look like travelling circuses with their Christmas light decorations, others slightly sinister because their bamboo gates are decorated with large swastikas (originally, an ancient Hindu symbol). A cluster of stained tents under a railway bridge is nothing but a shantytown.

On crossroad a tiny kiosk sells soap, cookies, water, toys, bags, sarees, and beads and other religious nick-nacks. Electricity poles and fences are wallpapered with posters advertising gurus and swamis. Every single one of them is sporting a bushy beard.

Some scenes are medieval. On the shoulder of a road a naked sadhu lies on a bed made of thorns, not unlike a fakir from a comic book. Nearby a group of leper beggars display their abscessed wounds to passers-by.

Next to an open ”shitting field” a pool-sized pond spreads urine stench into vicinity. In wintertime it hardly ever rains, so the air is blurred with fine dust that blackens nostrils and tickles throat. Most visitors get respiratory symptoms after a day or two, so cough syrup is a popular remedy at roadside clinics.

Deafening, maddening noise is everywhere. Music echoes, cars and motorbikes honk, police whistle, and mobile phones ring. A plastic cow statue, standing in a decorated carriage, lectures loudly against meat-eating.

Thousands of loudspeakers hang from electricity poles. They blast non-stop announcements from the missing persons office.

Lost and found

Frantic crowd swarms around the poor clerk behind his desk. People push small pieces of paper in front of him from all directions. Slips have names written on them: of wife, husband, child or maybe old mother. Loved ones who have gone missing.

”During past 3 weeks we have helped 17 000 people to find their families”, explains Umesh Chand Tiwari, the president of an NGO that runs lost people’s office. ”We provide food and shelter, and let them make loudspeaker announcements in their own languages. Usually it takes maximum couple of days before relatives come and pick up their lost family member.”

Getting separated from a group can be serious. Many of the pilgrims don’t have cell phones or money – they might not know how to speak Hindi or even read. Travelling alone to a home village on the other side of India would be an overwhelming challenge for the elderly people squatting at lost and found office.

Suddenly a gray-haired lady rushes towards the gate. She wraps her arms around a baffled man who’s just stepped in and begins to weep. Onlookers smile at this miracle of reunion, but husband looks embarassed. He tries to explain that the couple has been separated only for half an hour. They’ve just arrived and got lost on the way to the main bathing area.

Holy water

There’s a simple trick to finding Sangam, the most auspicious bathing spot: just follow the empty water canisters. They’re sold in every street corner, and each pilgrim carries a container or two.

”We drink river water during the festival and carry it back home with a big jug”, explains Rajasingh Phakur. He has just filled ten bottles with his brother Hanuman. ”If a neighbour asks, we share with him. We would never sell holy water.”

Ganges is one of the most polluted rivers of India. Toxication levels are sky-high, and the ancient practice of dumping half-cremated corpses into the river makes the situation even worse. Many environmental organizations and religious leaders have been preaching for protecting Mother Ganga, but mostly to no avail.

”Water is not dirty”, the brothers argue. ”It’s only dusty.”

Around us thousands of pilgrims seem to agree. They strip to their underwear, wade into the knee-deep water, and dip under the surface. Then they slurp water from their palms and pray towards the setting sun.

Sangam means confluence. This section of the river bank (or actually a spot slightly further from the shore) is considered especially divine. It’s the meeting point of three holy rivers: Ganges, Yamuna, and mythical Sarasvati. Bathing here will wash away sins.

The ecstasy of being at such a holy place is tangible. Even dozens of foreign photographers, prowling for the money shot, can’t disturb the pilgrims who looking for salvation.

If bathing in Ganges is the heart of Kumbh Mela festival, then sadhus are it’s soul.

Holy but not saint

A man whose naked body has been smeared with ash stands beside a roadside altar. Carefully he winds his genitals around a wooden stick. Some passers-by stop to watch but many move on, thinking there’s nothing unusual to see.

In the West the naked man would be locked up, but in India he’s regarded as a saint.

India has millions of sadhus, men and women who are believed to be holy. Some gurus, babas or swamis have thousands of followers and remind of American TV preachers and other cult leaders. But majority of holy men lead a much simpler life. They are hermits who meditate in remote caves or roam around the country visiting holy places.

Kumbh Mela provides a rare opportunity to meet sadhus. Many of these creatures resemble of shamans with their dreadlocks, long beards, three-prong tridents and hashish pipes. Devotees think they have a broadband connection to the spirit world.

The man playing with his genitals is a naga (naked) sadhu. Instead of wearing clothes, Shiva-worshipping nagas rub onto their naked bodies ash that symbolises death and reincarnation. They smoke hashish and chastise their genitals which represent contaminating sexuality. Subjugating penis, for example by rolling the organ around a stick or sword or by hanging weights from it, is believed to transform sexual energy into spiritual one. Another reason for this shocking practice is to demonstrate how spirit can overcome pain.

There are even more extreme rituals. Some sadhus take a vow to hold their arm in the air or stand up for years, never cut their hair, or utter a word for years.

Silent Sadhu

”I haven’t spoken since 27 December 2008”, the man with sparse teeth explains. ”My guru encouraged me to begin a fasting of silence and maintain it as long as I could. He will probably scold me for giving this interview.”

Communicating with a man who doesn’t speak is challenging. Fortunately he knows how to write, but forgets to scribble down his name in the notepad. Let’s call him simply Silent Baba.

”I used to work as a clerk in the Ministry of Health”, Baba writes. ”But my boss didn’t like me because I was praying aloud all the time. I had to choose between a career and my faith. I quit my job and became a sadhu when I was 36. Now I live in a cave.”

Silent Baba hasn’t forgot his motherland: ”Even though I couldn’t work as a public servant, I can help India by praying. Many problems prevail in society, but because of divine mantras India is moving on.”

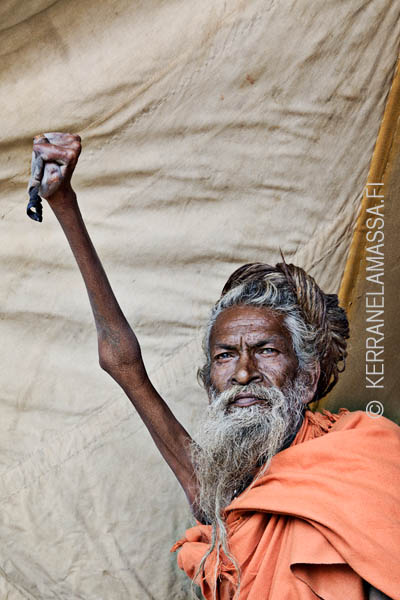

Near the gate of naga sadhu camp we pass an old man who’s holding his right hand up. The arm is nothing but skin and bone, and his long fingernails spiral like apple peels.

The man’s name is Amar Bharti Baba, and he has kept his arm up for unbelievable 39 years. ”It’s a flag that is raised to honour Shiva”, he told us when we interviewed him during previous Kumbh Mela 3 years ago. ”Once you raise it, you must keep it up.”

Now the man couldn’t be bothered with questions. He’s too busy puffing away with his hashish pipe.

After witnessing feats like penis yoga or shriveling one’s limb on purpose one can only wonder if there’s a difference between a religious ritual and a show designed to awe spectators.

Wall of death

The wooden cauldron, 10 meters deep and 20 in diameter, is trembling. Three battered Maruti cars and four ancient motorbikes chase each other around a near-vertical wall in a dizzying speed. Noise from their motors blocks ears.

As if the show wasn’t hazardous enough, a rider with beige shirt loosens his grip from handlebar. He stands up and begins to collect tips from the spectators as he zips by. After securing handful of 10-rupee notes between his lips he defies the laws of gravity by lounging sideways on the saddle.

Welcome to Maha Kumbh Mela’s funfair.

Just a couple of kilometers from bathing areas and sadhu camps unfolds the material world. Triveni Road is lined with up-market camps with hot showers and a la carte menus, temporary shopping centers packed with colorful sarees and gold jewelry, and even a couple of ATM’s. Beside them a ridiculously loud expo ground displays tractors and excavators. The funfair has a ferris wheel, magic show and cotton candy.

After the thrilling show we meet the rider in beige shirt. Mohammad Samir, 19, has been riding a motorbike since he was 12 years old. It’s a family business: Samir’s uncle works at the funfair and his younger brother is a stunt rider, too.

Their motorbike show arrived at Allahabad two months ago. It’s an opportunity to make some serious money. ”During the busiest days we’ve had 50 5-minute shows. I haven’t even had time to bathe in Ganges yet.”

Once in a lifetime

The main bathing day, Mauni Amavasya Snan, is an overwhelming experience. In early hours thousands-strong hordes of sadhus and devotees begin to march one by one to Sangam, and at sunrise the place resembles of a riot. Police tries to control crowds, cleaners pile up muddy shoes that pilgrims have lost while bathing, and noise and half-naked sweaty bodies push from every direction.

The holy river turns murky when everybody scrubs their sins and bad karma off simultaneously. A promise of salvation is so alluring that participants are willing to risk their lives.

When a chubby woman in green saree falls it seems certain that she will be trampled. Then three men manage to pull her back on her feet. The woman is crying, eyes wide from panic.

India’s religious festivals are infamous for deadly stampedes. The worst accident in Kumbh Mela’s history occured in 1954, when 800 people were trampled to death. Fortunately nothing of the sort happens at the bathing area this time around, but in the evening we hear sad news: 36 people have perished in a stampede at Allahabad train station.

Officials estimate that a whopping 30 million people – more than the population of Nordic countries combined – visit on main bathing day. It’s impossible to say how accurate the staggering numbers are, but standing on a fence one can see a limitless sea of people expanding to all directions.

It’s like a wildebeest migration in a nature documentary. Millions of individuals, wandering to the same place in search of salvation, become one mass. It’s a humbling experience to be part of such a herd.

PRACTICAL INFORMATION

Mela festivals

Kumbh Mela is celebrated every three years. The location rotates between four towns: Nashik, Ujjain, Haridwar and Allahabad. Next Kumbh Mela will be held in Ujjain in April-May 2016.

Every 12 years the festival grows into even larger Maha Kumbh Mela. It’s always in Allahabad, next time in 2025.

Several million pilgrims flood Allahabad during annual Magh Mela. The festival is smaller than Kumbh Mela, but otherwise very similar. It’s held every year from mid-January until the end of February, next time in 2016.

Visiting a Mela

Allahabad airport serves a limited number of domestic flights. A better connected airport is in Varanasi, 150km away. A train from Delhi to Allahabad takes 7-10 hours and costs 15-20€.

Mela grounds are located several kilometres outside of Allahabad town. There are no permanent buildings, so visitors sleep at tent camps.

A typical camp has dozens of large tents (with attached or shared bathrooms) and a canteen that serves buffet meals. All food is vegetarian, and alcohol is strictly prohibited in Mela grounds.

Many camps have their own website with a reservation system or can be booked through a travel agent. One of the easiest accommodation options is the camp run by Uttar Pradesh Tourism office. The cost in 2013 was roughly 50€ / person. It’s a good idea to book several months ahead.

Weather in January and February is dry and dusty. Temperature in the afternoon can be up to 30C and at night down to 10C.